Mobility

The workshop and the statistics make it possible to establish that walking and cycling in summer are widely used for the movement of young people.

Active transports comprise 50% of the neighbourhood's principal mode of transport. As a reference, 30 minutes is needed to walk the width of the neighbourhood and 10 minutes to walk its height. This time is reduced by half when cycling. BIXI offers close to 20 stations to the burgz, which makes it appealing and useful to many.

Spaces dedicated to active transportation

Public parks, illustrated in the diagram, are mobility tools as they are actively part of the commuter paths and embedded in the dwellers’ way of moving.

Today's parks result from many causalities, including the first offered to the population on religious grounds, squares and major renewals or initiatives dating from early 1879 to today, illustrated below by hatchings.

Diagram1 : Chronological evolution of parks used as crossings and leisure Diagram 2: Collage of significant markers of space at the origin of the parks

The past left an important legacy to today’s Little Burgundy fabric. The parks used today for commuting are marked by the old Canadian National Roadway crossings axis, shown above as lines and below in the video. The analysis denominates this typology of the park as a path-park. In some instances, the dwelling's main doors face the path-park making it a primary access point.

Left: Walking the path-parks

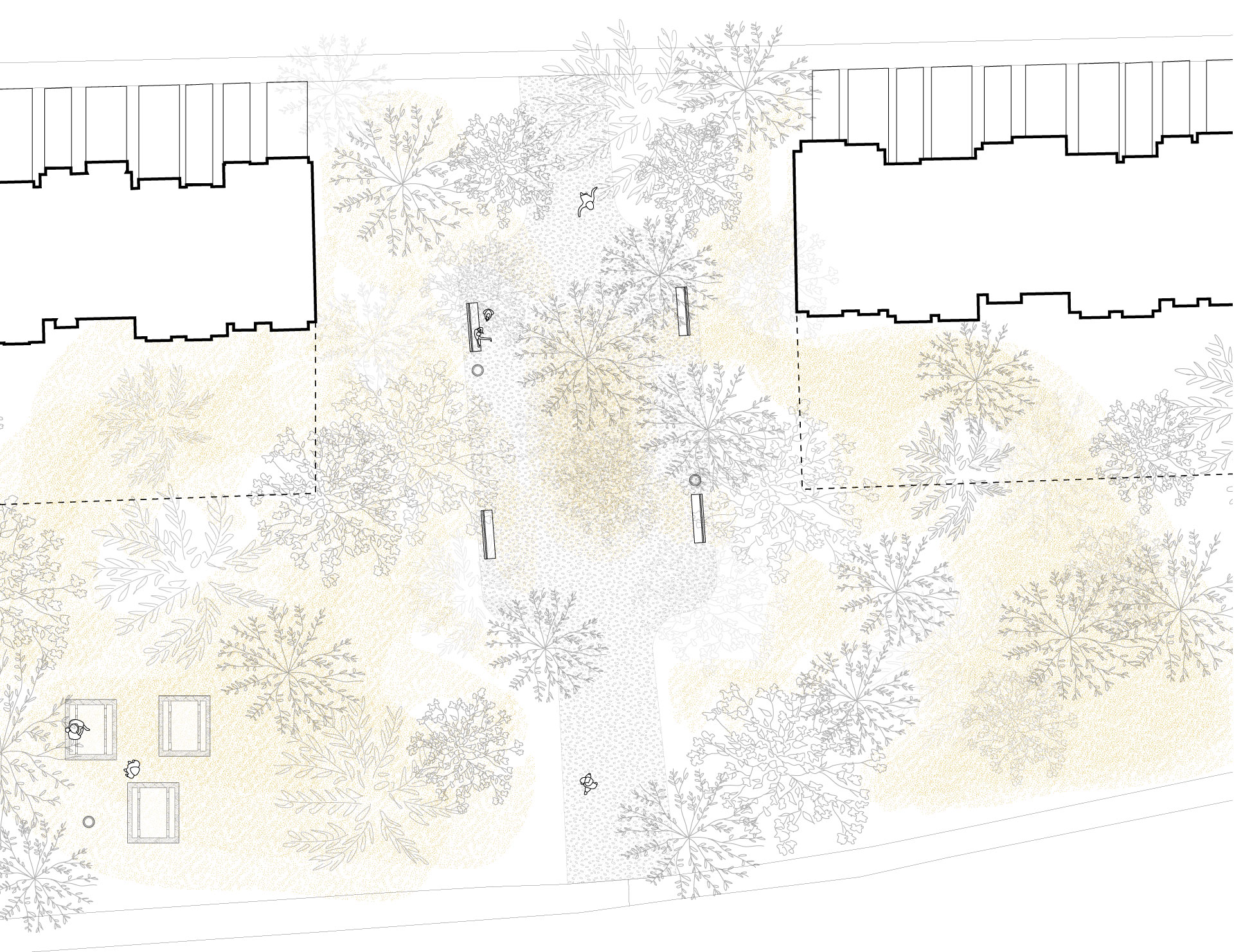

Right: Path-park type including possible amenities

These examples are of the many connectors resulting from the restructuring of the past, facilitating pedestrian traffic through the district. This intervention offers residents micro-parks and passageways, creating a rich and porous urban fabric. However, this path-park typology only partially encourages the long use of the space over an extended period, although some host benches. It is primarily a transitional space to take a short break while commuting. Overall, Little Burgundy parks present great opportunities for engagement with the community as they are actively part of one’s commute or leisure time.

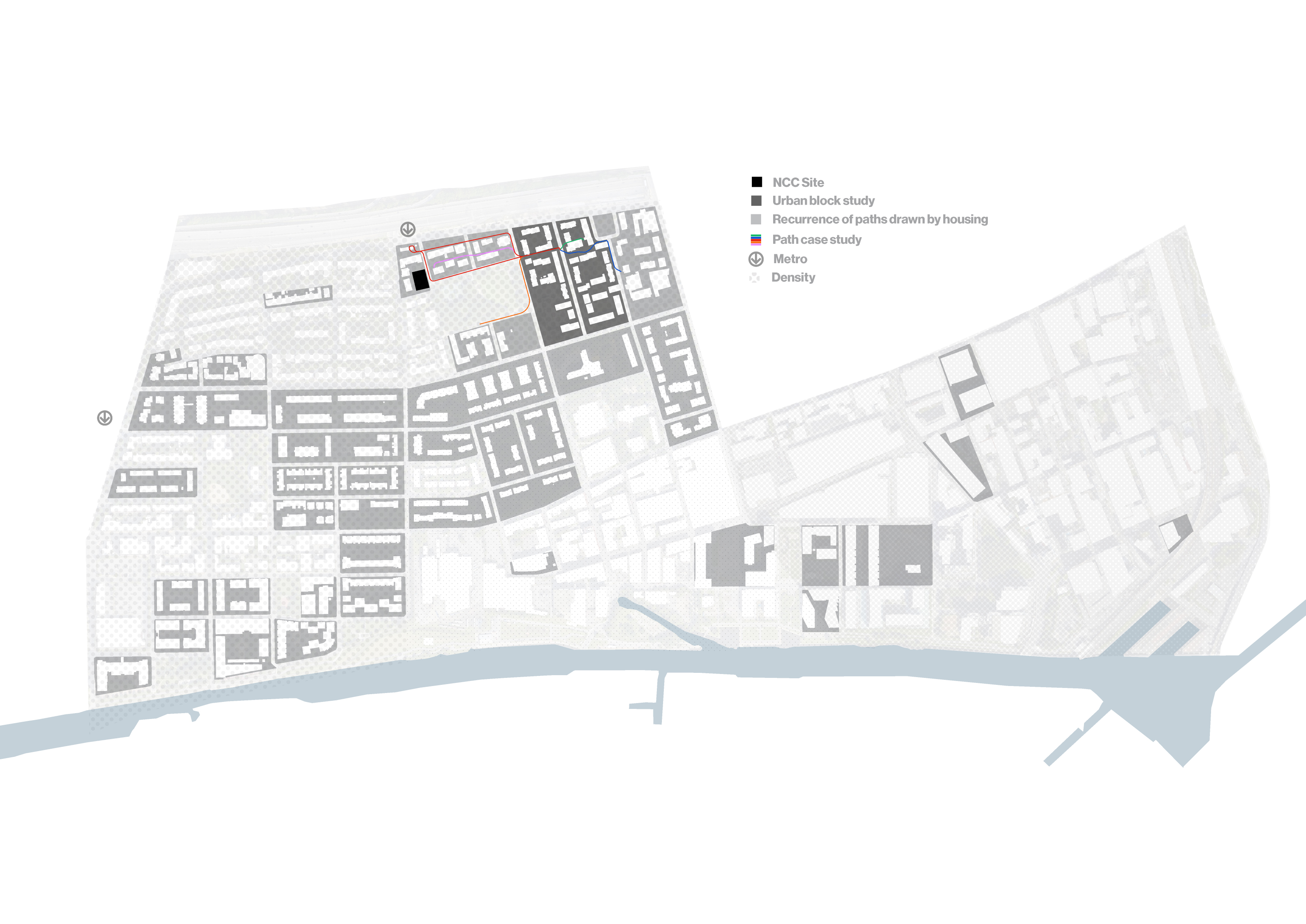

Likewise, architecture contributes to the community’s mobility. Combined with preserved subdivisions of the past, the 1960s social apartment block typology and layout, that is, blocks often away from the street and not occupying the entirety of their lot. They deploy a highly porous fabric, both physically and visually. They, thus, participate in a rich and complex set of layered networks. The participants were asked how they got to the workshop and the majority responded that they traveled through the said paths.

Likewise, architecture contributes to the community’s mobility. Combined with preserved subdivisions of the past, the 1960s social apartment block typology and layout, that is, blocks often away from the street and not occupying the entirety of their lot. They deploy a highly porous fabric, both physically and visually. They, thus, participate in a rich and complex set of layered networks. The participants were asked how they got to the workshop and the majority responded that they traveled through the said paths.

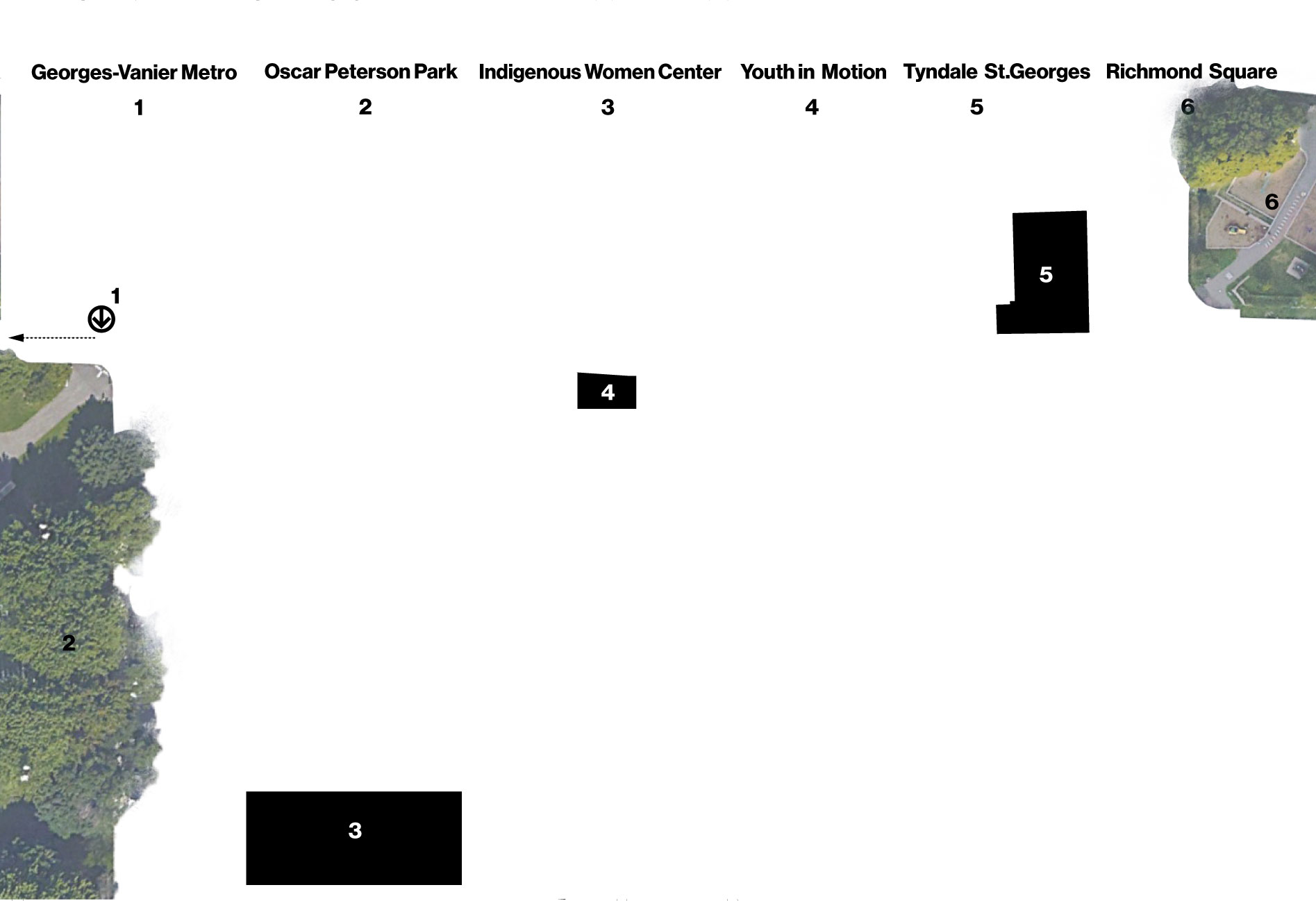

Diagram 1: Networks activated by the social housing block typology. The extract shows how some of the participants reached Youth in Motion on the day of the workshop.

Diagram 2: Legend of the present landmarks in the path case study.

Recreation of three paths to get to the workshop

The layout of the social housing blocks emerges an important network of sidewalks communicating with each other, the inner courtyards and the street. The network allows the pedestrian to walk around and quickly take shortcuts. The type of scenario is common to the neighbourhood’s housing typology and in the social interventions pictured above in the reccurence of pattern diagram.

Diagram 2: Density of the neighbourhood

The proportion of built versus unbuilt space on these urban blocks is about 40 percent in the interventions qualified as porous of the past and the most recent. This basic ground occupation results in a reduced urban density, but can be compensated and increased by building in height, as in the Griffintown sector.

Walking the housing paths

Noticed in the ilôt St-Martin, fences were erected well before the 2000s, which can question the appreciability of physical porosity by the citizens. Is this porosity desirable or rather harmful? As outsiders of the community and with discussions with Youth in Motion members, it is suggested that the fences offer a feeling of safety. The area is quite occupied by families as noticed in site surveys. The site is also quite close to many fast arteries and high traffic of passers-by walking to or from public transportation.

Most of the teenagers present in the workshop mentioned they used the metro as their way to commute to farther distances. Conversly, the adults prioritized private automobiles as their primary mode of transit.

Most of the teenagers present in the workshop mentioned they used the metro as their way to commute to farther distances. Conversly, the adults prioritized private automobiles as their primary mode of transit.

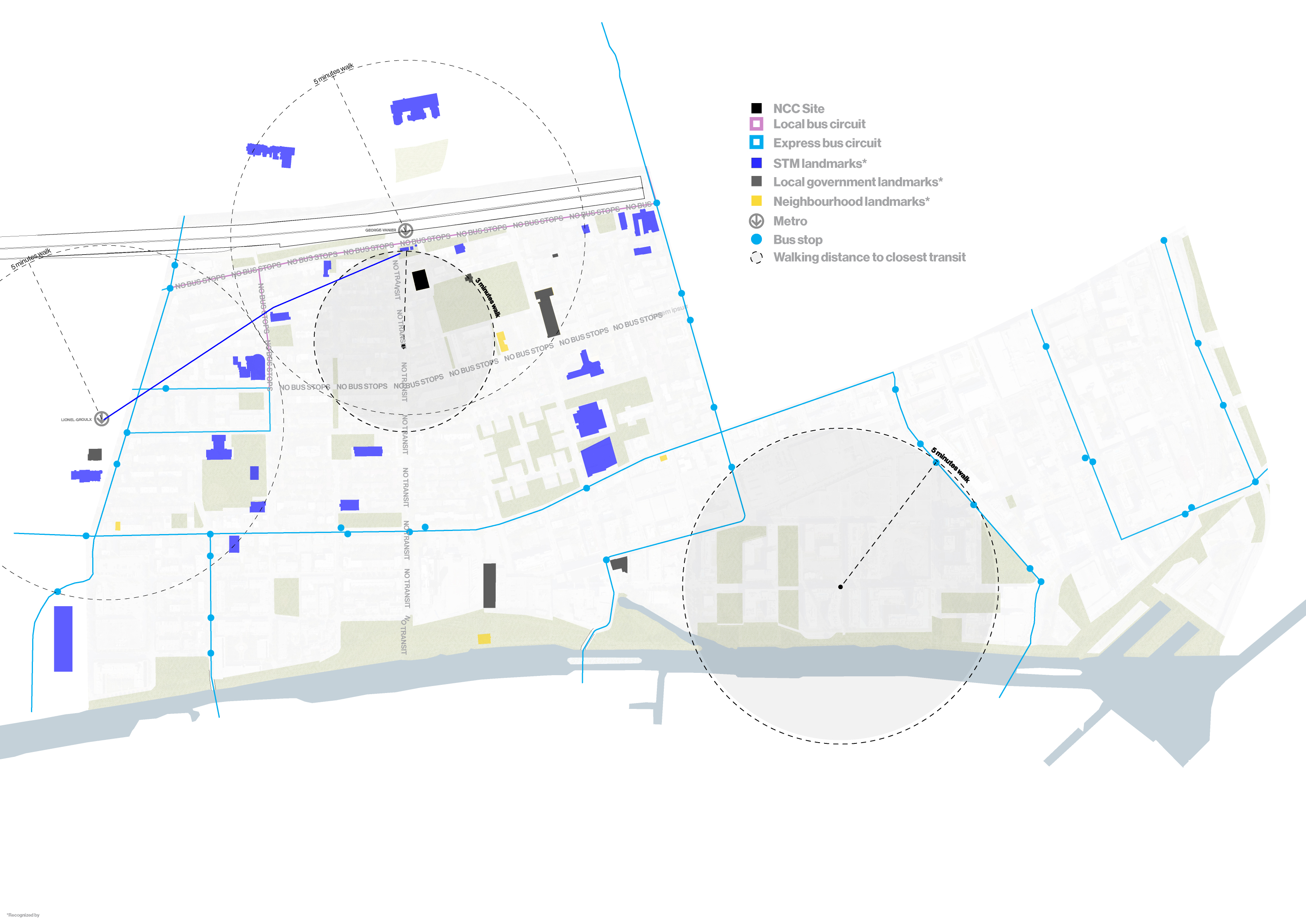

Transit map

Transit map Central Little Burgundy is not well served by the Montreal public transit system. The closest bus station from Georges-Vanier’s metro is 500 meters away, or about 6.5 minutes at walking speed, which can complicate transit for the elderly or youth, and for many during the winter months. The explorations of plausible way to get to Lachine Canal from Georges-Vanier metro station highlighted that no options are possible, except by a 10 minutes walk. Alternatively, going to Lionel-Groulx metro station would take twice the time and would still require a considerable walk.

Similar situations emerges when looking at the public transit service. Areas are relatively far from bus stops and complicate active travel for many. Interestingly, the local transit system organization, la Société des transports de Montréal (STM), recognized close to every landmarks, including the parks, in its lastest Plan de quartier, neighborhood map.

Being in a particular area in which close to no businesses or non-residential spaces are to its direct sight Metro Georges-Vanier’s setting is a functional space. With no motives to stay or occupy adjacent spaces, the public space is ghostly.

Similar situations emerges when looking at the public transit service. Areas are relatively far from bus stops and complicate active travel for many. Interestingly, the local transit system organization, la Société des transports de Montréal (STM), recognized close to every landmarks, including the parks, in its lastest Plan de quartier, neighborhood map.

Being in a particular area in which close to no businesses or non-residential spaces are to its direct sight Metro Georges-Vanier’s setting is a functional space. With no motives to stay or occupy adjacent spaces, the public space is ghostly.

Georges-Vanier Metro station from inside out

The environment of this particular metro station would benefit from activities and space taking up the space of the street and the square to increase its liveliness and safety. The NCC site being in direct relation for the majority of commuters represents a potential in the requalification of the transitional space.

Alltogether, the set of soft and public mobility makes the neighborhood accessible and connects quite easily to farther extends in South-West and Montreal.

Alltogether, the set of soft and public mobility makes the neighborhood accessible and connects quite easily to farther extends in South-West and Montreal.