MSoA — ARCH673 — W23

Remediation Gardens

a study on urban land detoxification

By Tiffany LauWe look to the land to provide for us. In Remediation Gardens, themes of placemaking and habitation are explored through the community’s relationship with the land. Historically, the NCC acted as a place of respite for the people it served. Its role as a beacon of cultural preservation allowed the community to anchor themselves in the land they inhabited.

Honouring this act of communal relief, the proposal centres on facilitating the healing of people and site through adapting the land to aid the community with issues they currently face: food inequity and insecurity.

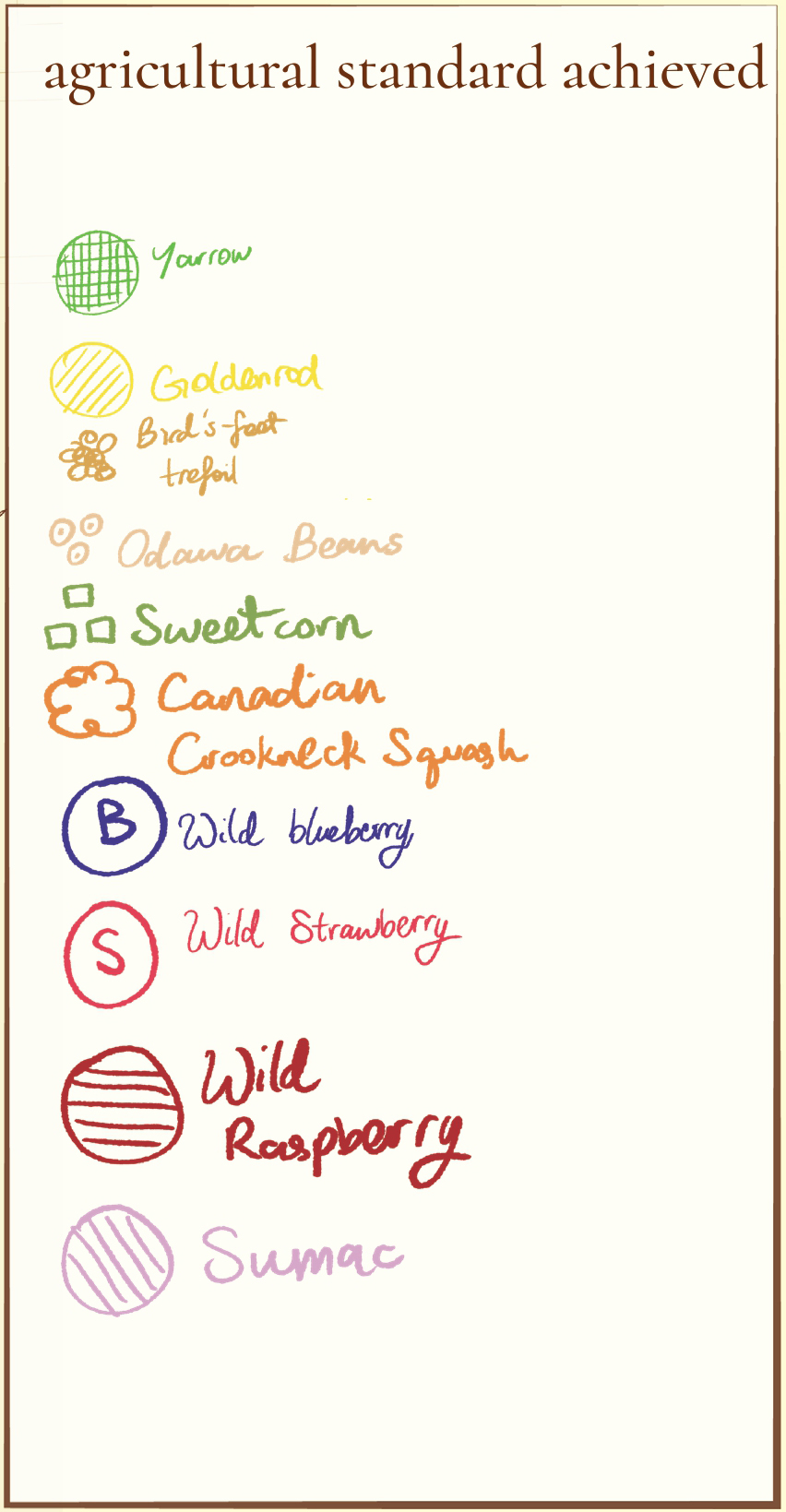

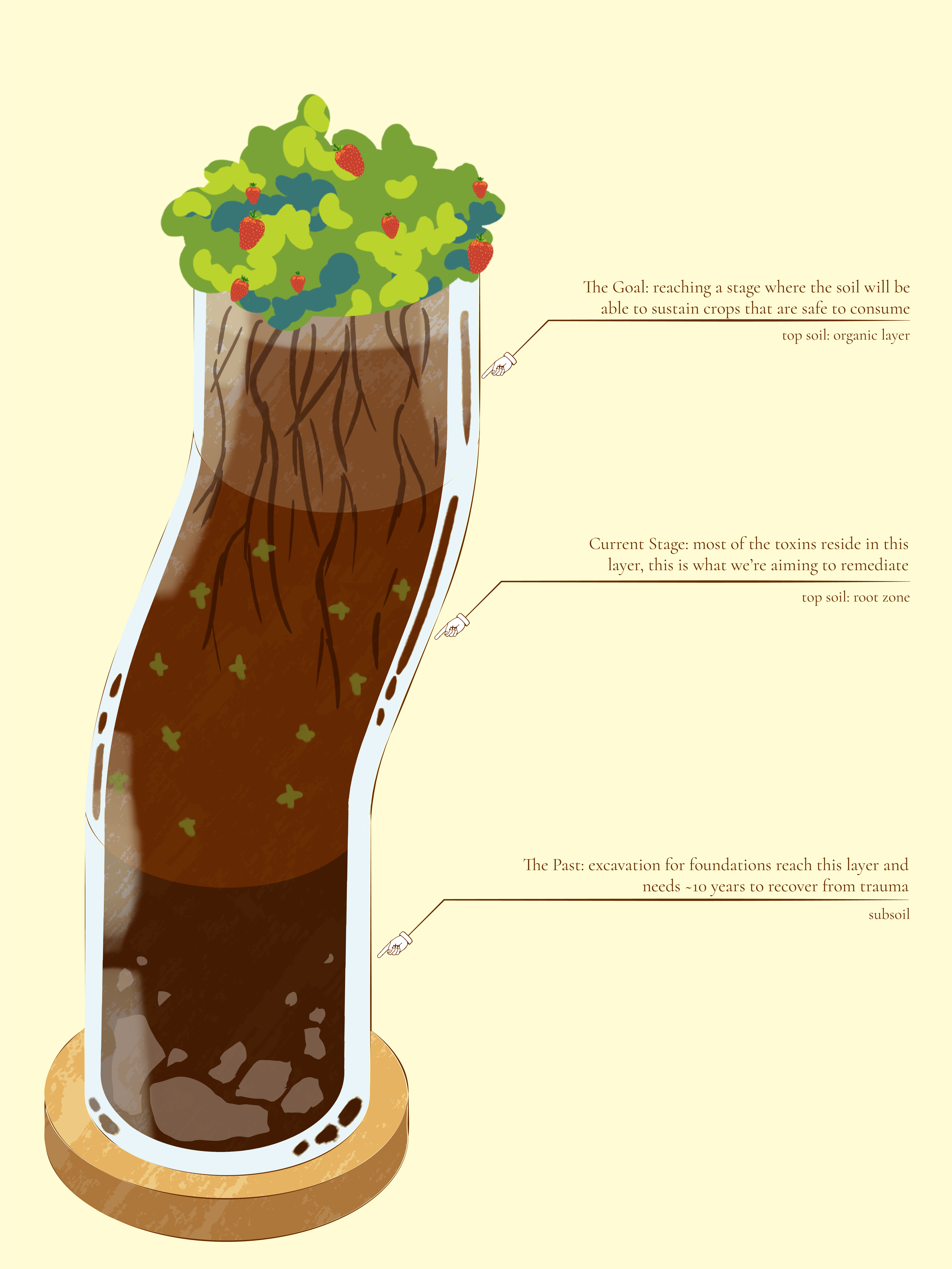

Discussions of agricultural independency during our community engagement workshop expressed a particular desire for agency over the food one consumes. With the nearest supermarket located a 20 minute drive away from Little Burgundy, it brings forth the question: why is health considered a commodity? Pursuant to these growing food concerns, the proposal utilizes phytoremediation to facilitate learning on three fronts: teaching the community a) how to grow food; b) the different phases of soil remediation and what crops could be sustained at each level; and c) the time it takes for land to recover naturally from trauma. Unlike community gardens with their year-long waitlists, once an agricultural standard is achieved on the site, the land will continue to be used as a public growing plot for learning—allowing for this knowledge to continue through generations. The ultimate goal is to be able to learn how to use the soil in your own backyard to safely grow food.

Discussions of agricultural independency during our community engagement workshop expressed a particular desire for agency over the food one consumes. With the nearest supermarket located a 20 minute drive away from Little Burgundy, it brings forth the question: why is health considered a commodity? Pursuant to these growing food concerns, the proposal utilizes phytoremediation to facilitate learning on three fronts: teaching the community a) how to grow food; b) the different phases of soil remediation and what crops could be sustained at each level; and c) the time it takes for land to recover naturally from trauma. Unlike community gardens with their year-long waitlists, once an agricultural standard is achieved on the site, the land will continue to be used as a public growing plot for learning—allowing for this knowledge to continue through generations. The ultimate goal is to be able to learn how to use the soil in your own backyard to safely grow food.

〰

paths

What is the relationship between the path and the landit treads through? Paths have typically been a symbol of human impact but more than that, paths represent familiarity with the land. Whether it be your commute to work or the route to your favourite bird-watching spot, in either case, human emotion is intrinsically tied to the concept of the path.

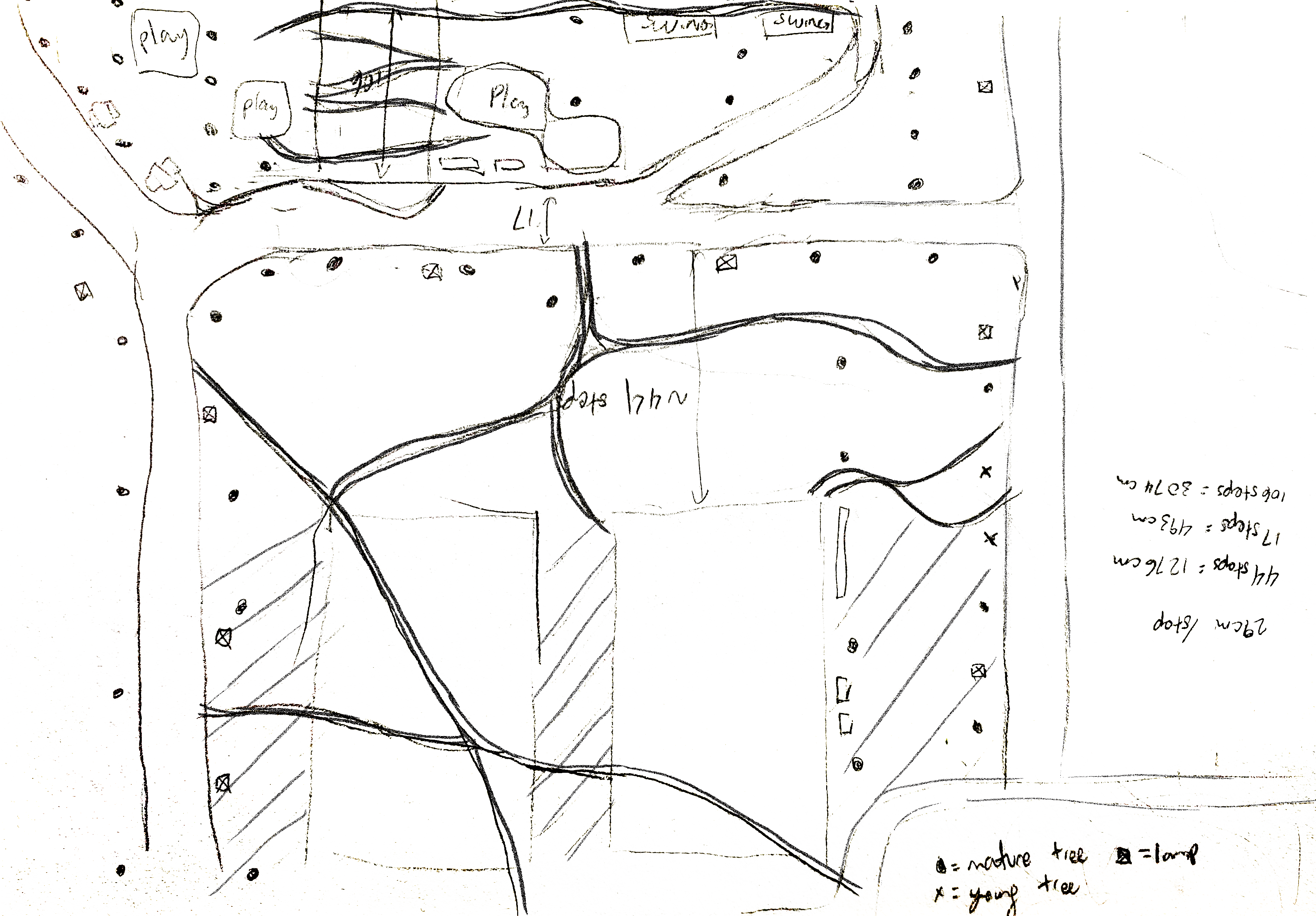

Early stages of this project looked at Oscar Peterson Park (formerly, Campbell Park), the heart of Little Burgundy. Having spent a cold winter day simply observing, it was interesting to note the informal rituals that exist through and around the park even in the dead of winter. A man taking his children to the playground; a teenager sliding through the frozen basketball courts as a shortcut to the other side; a woman trudging through the dimly lit park with two full bags of groceries. Few people may have frequented the park that day but the snow banks that pile high around these walkways tells a different story. Trekking over and cutting through paths, deep footprints set in the snow signify a sense of familiarity and of a ritual that persists despite its inconveniences. In the sketch above, such informal paths are traced and used to determine the design. Where the paved road has become redundant, a new “informal” path takes its place.

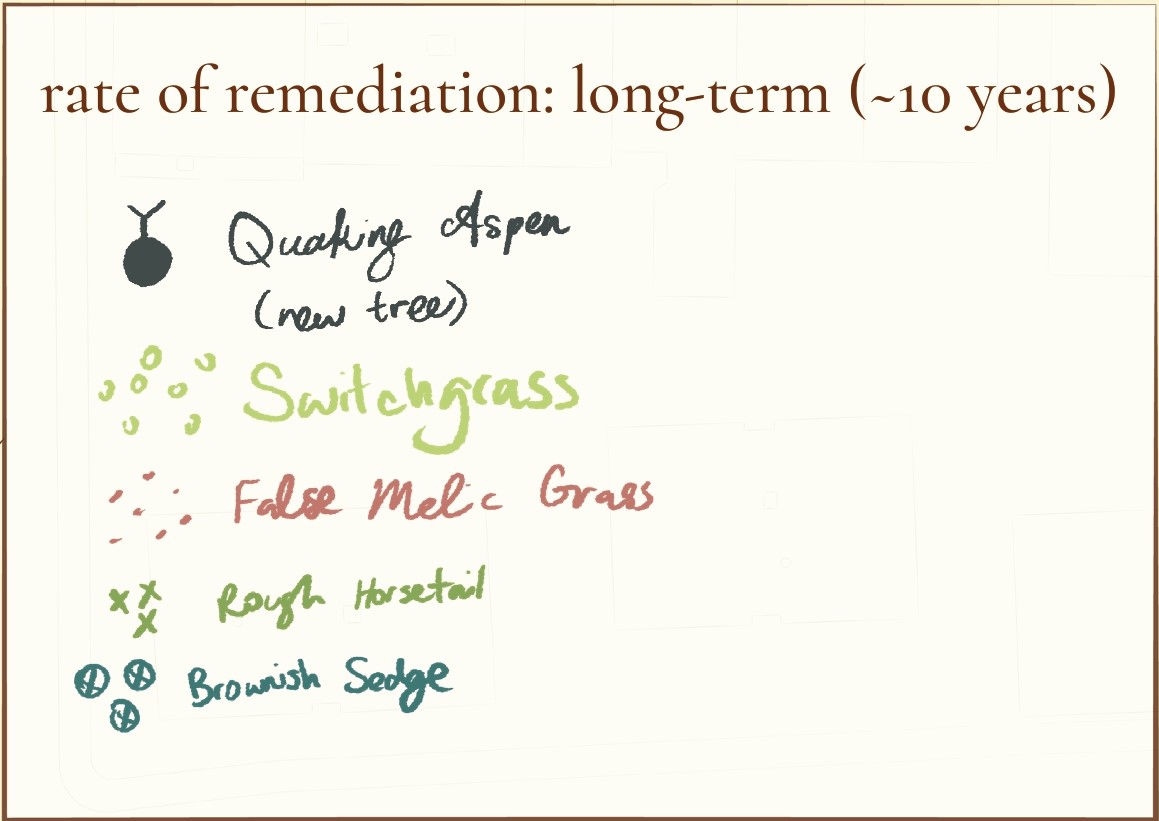

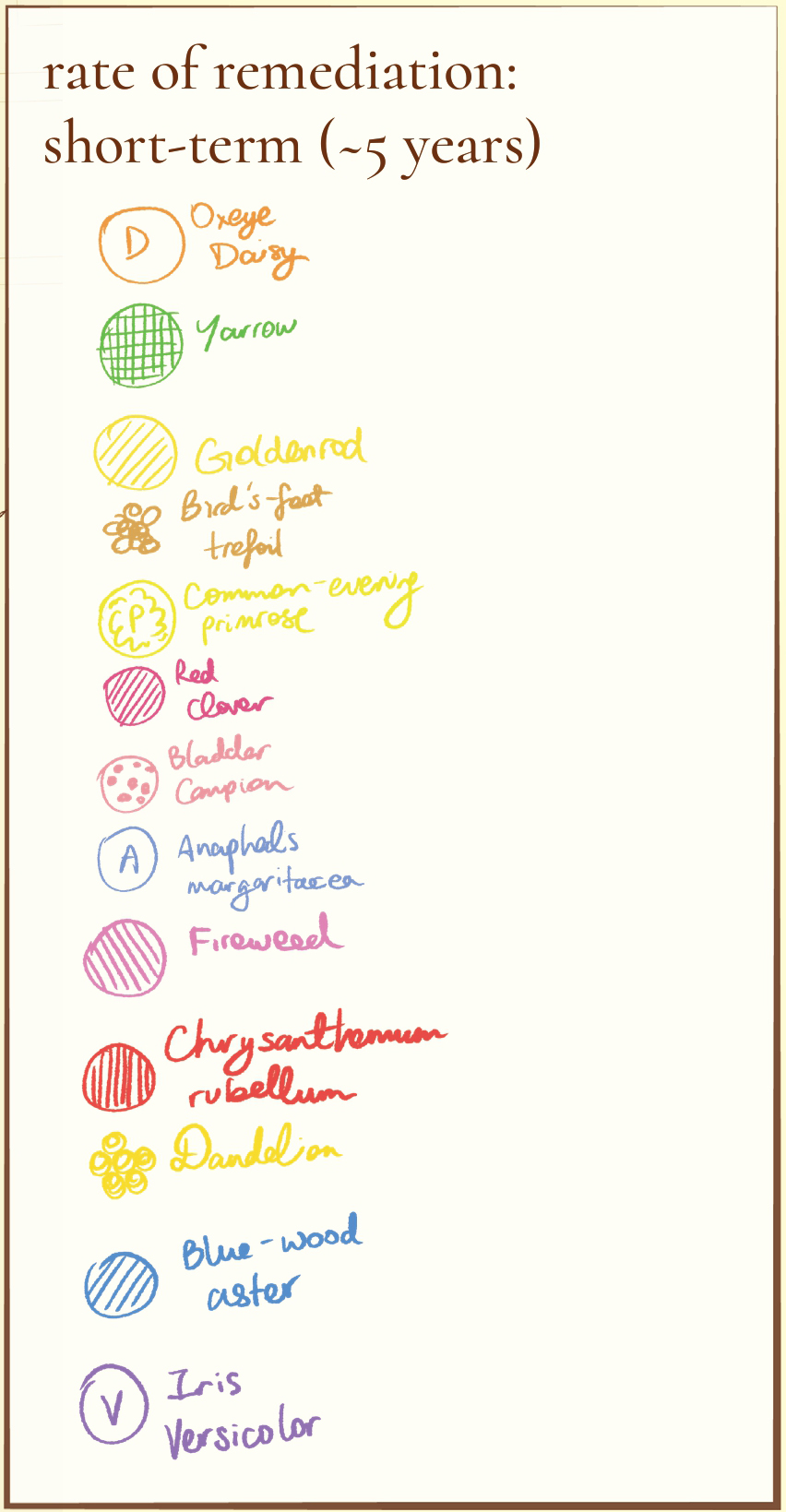

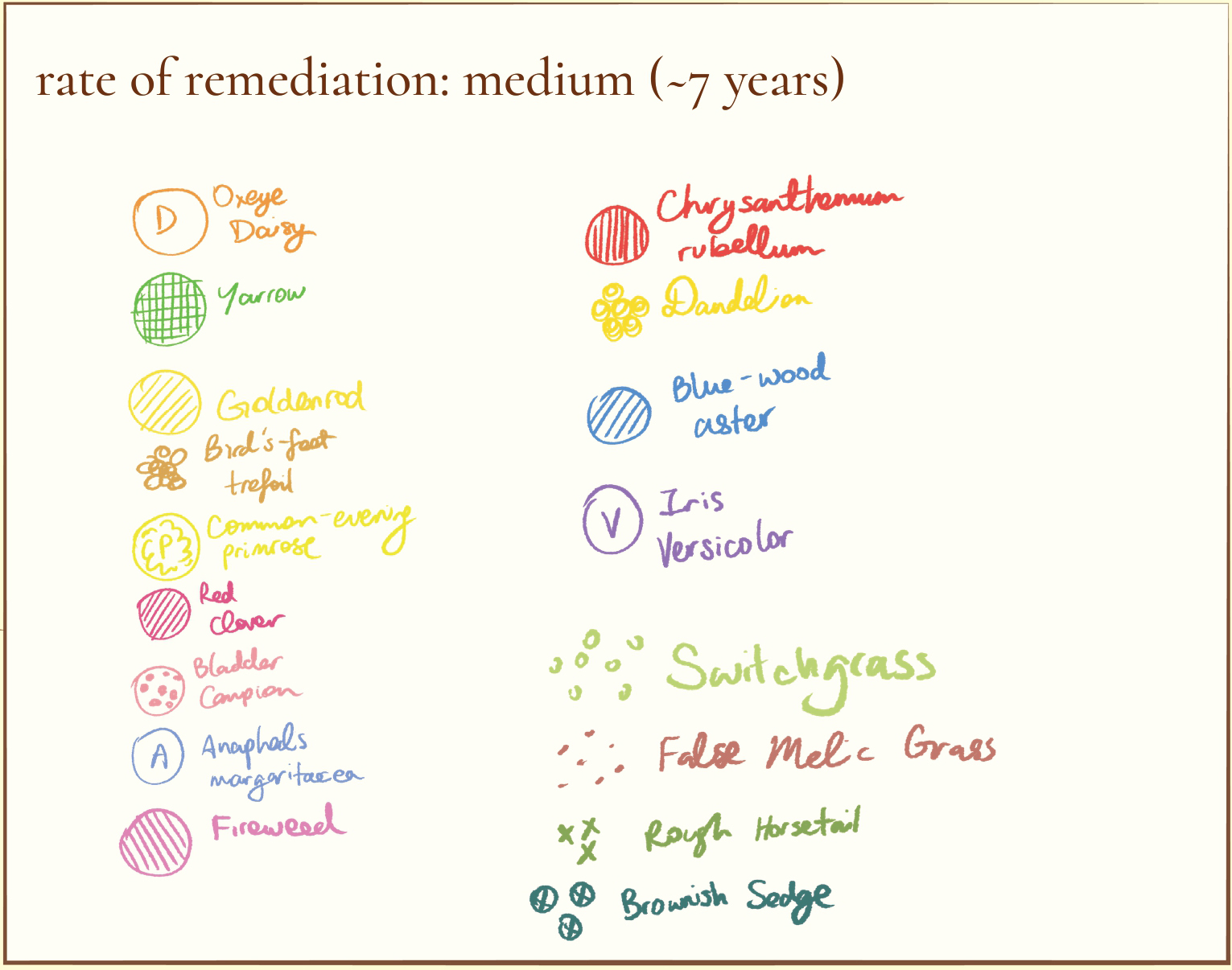

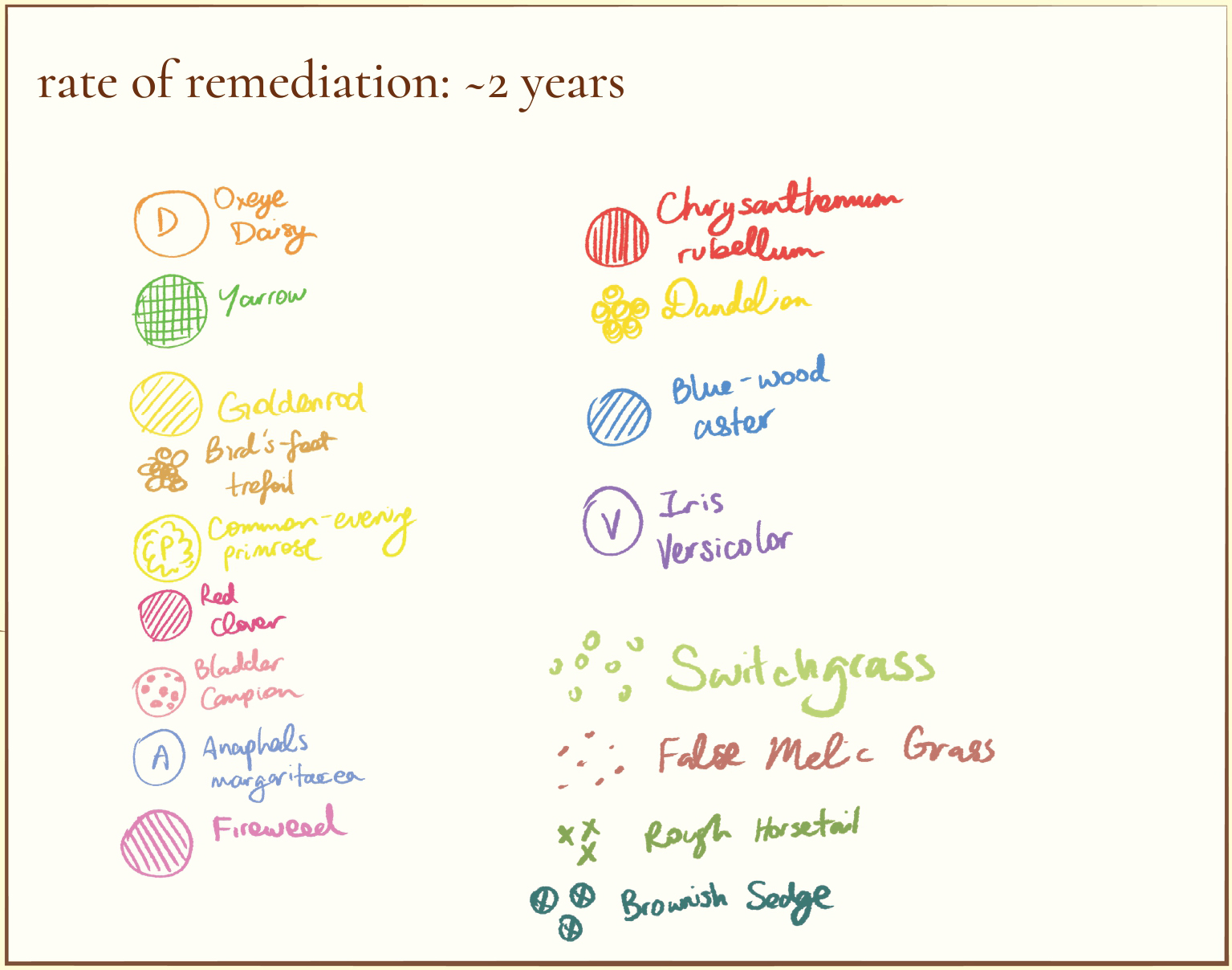

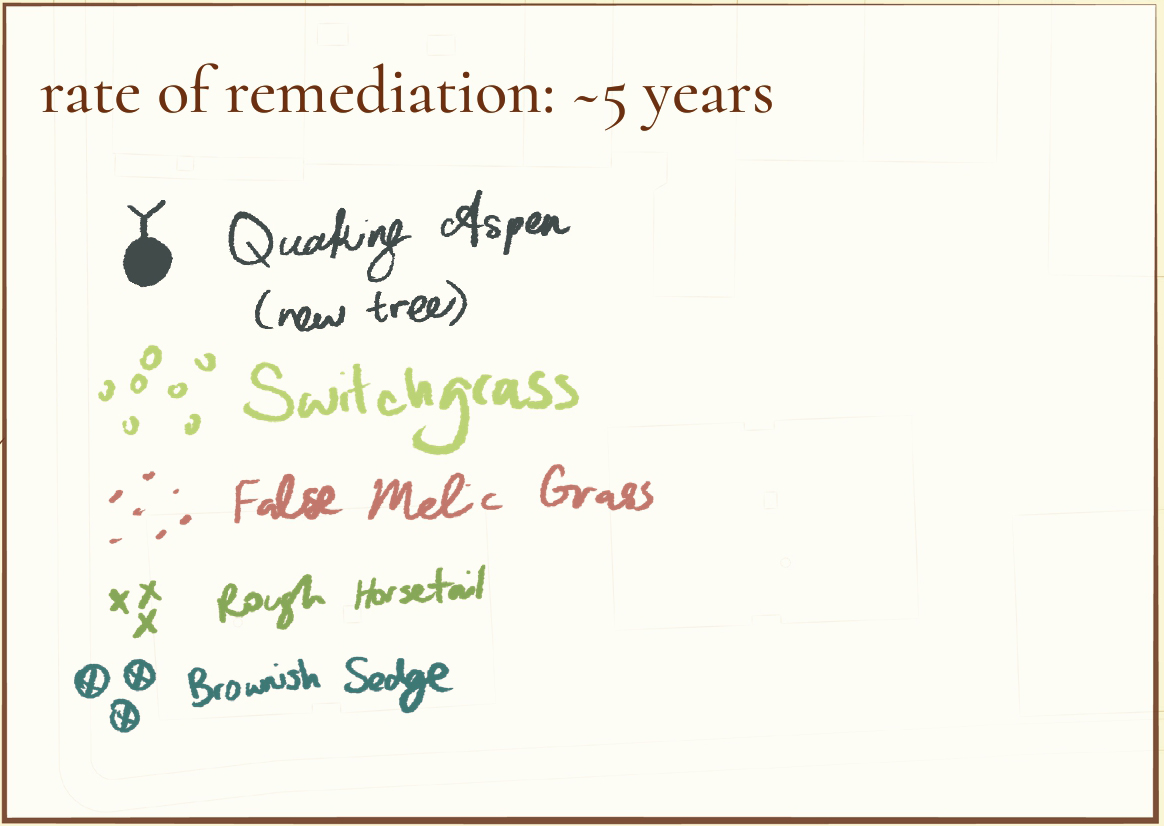

We begin at the site of the NCC and are carried through to Oscar Peterson Park by meandering walkways. Following these informal paths, old connections are recalled and new connections are created. These paths circle a variety of gardens all undergoing the process of phytoremediation. Dependant on its land use history, however, different lots have different rates of remediation and such is accommodated for in the plantings of various species that target its most concentrated contaminant. The site plans below depict an estimated time frame for the process of remediation and the range of crops that could be sustained with each stage:

Early stages of this project looked at Oscar Peterson Park (formerly, Campbell Park), the heart of Little Burgundy. Having spent a cold winter day simply observing, it was interesting to note the informal rituals that exist through and around the park even in the dead of winter. A man taking his children to the playground; a teenager sliding through the frozen basketball courts as a shortcut to the other side; a woman trudging through the dimly lit park with two full bags of groceries. Few people may have frequented the park that day but the snow banks that pile high around these walkways tells a different story. Trekking over and cutting through paths, deep footprints set in the snow signify a sense of familiarity and of a ritual that persists despite its inconveniences. In the sketch above, such informal paths are traced and used to determine the design. Where the paved road has become redundant, a new “informal” path takes its place.

We begin at the site of the NCC and are carried through to Oscar Peterson Park by meandering walkways. Following these informal paths, old connections are recalled and new connections are created. These paths circle a variety of gardens all undergoing the process of phytoremediation. Dependant on its land use history, however, different lots have different rates of remediation and such is accommodated for in the plantings of various species that target its most concentrated contaminant. The site plans below depict an estimated time frame for the process of remediation and the range of crops that could be sustained with each stage:

... at present ...

... in 5 years...

... in 20 years...

For purposes of applicability, Oscar Peterson Park’s history as a residential zone ensures that the soil from these designed lots and the soil found in the current neighbourhood are similar in composition.

〰

plots

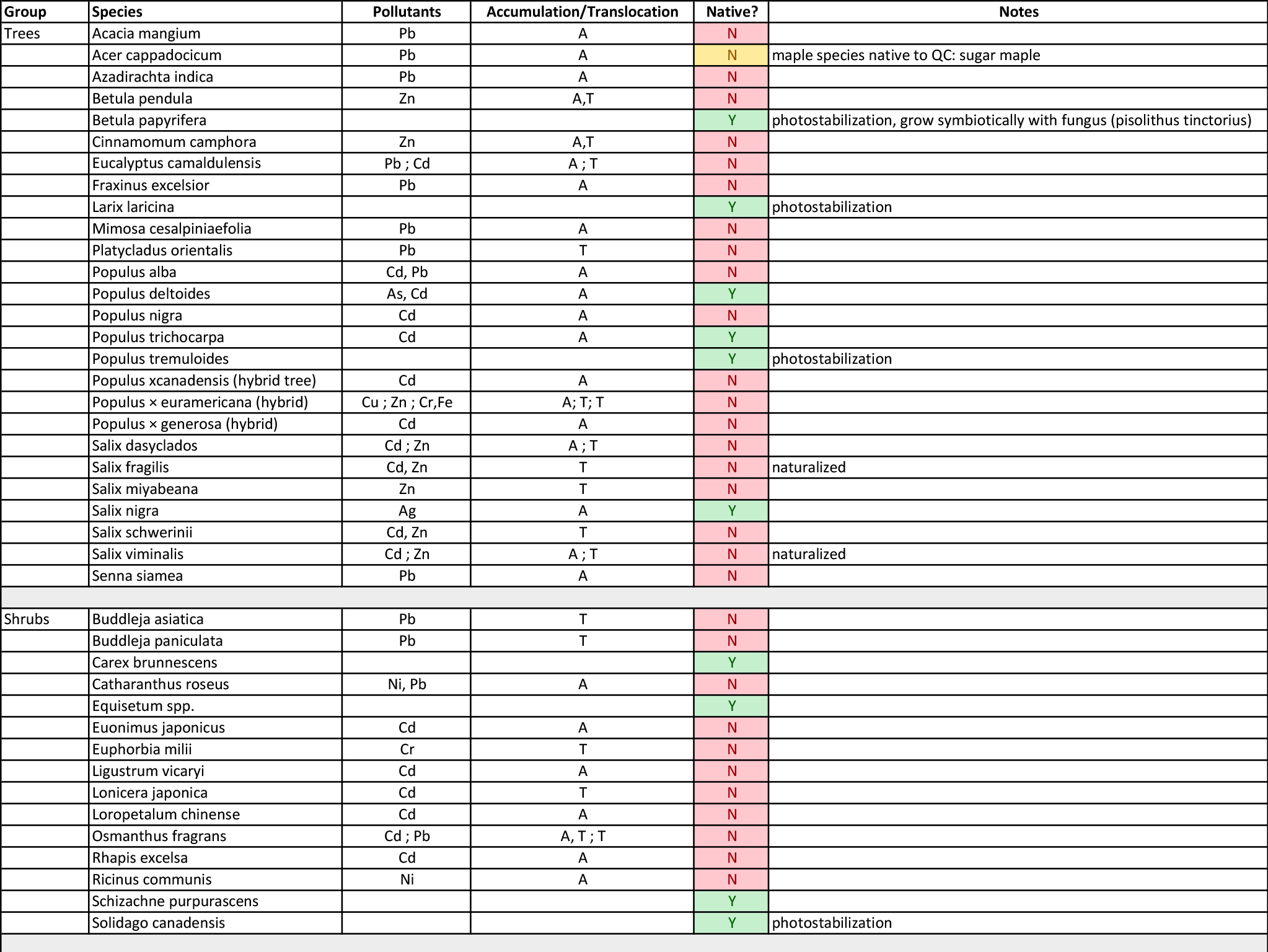

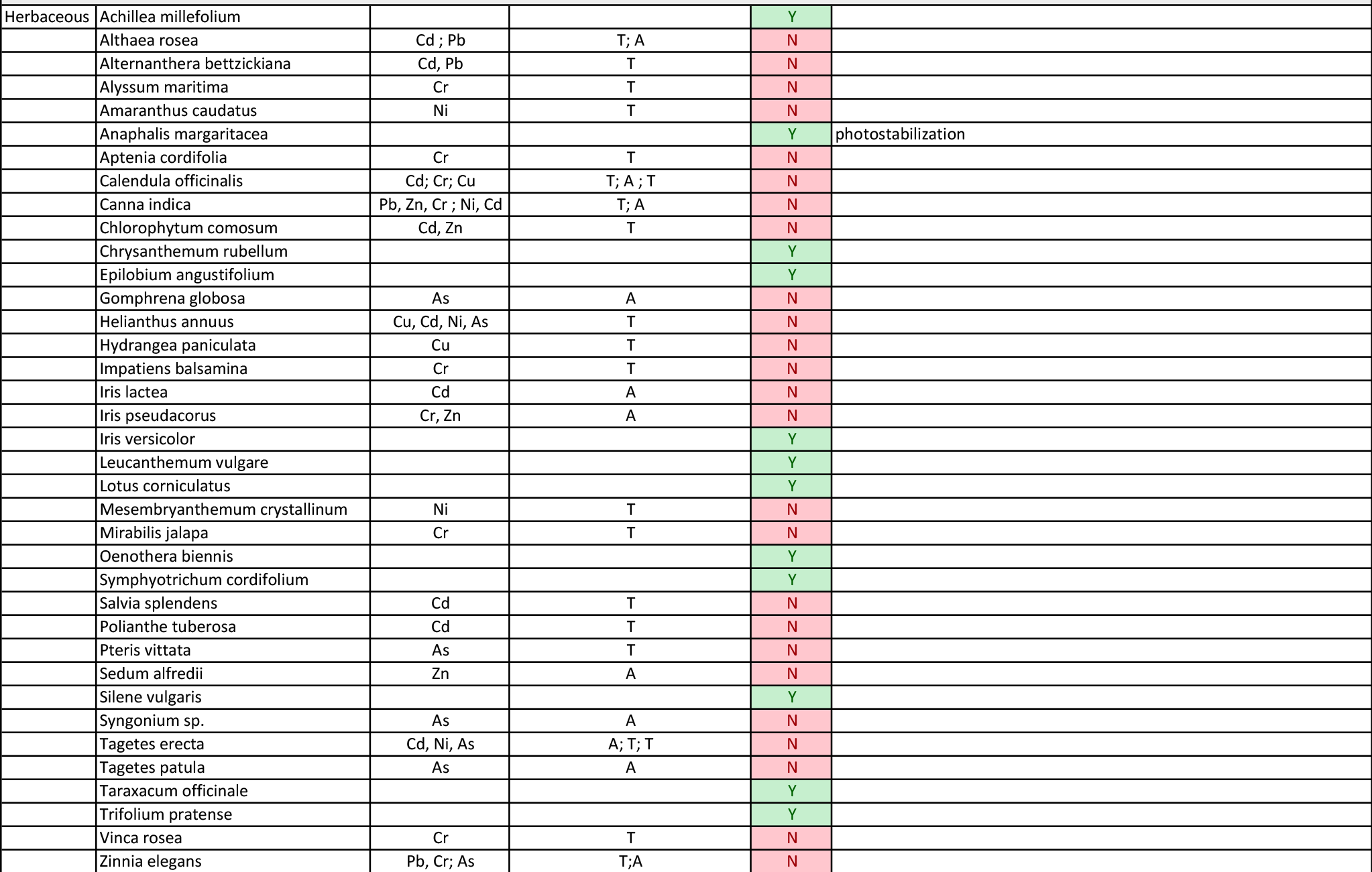

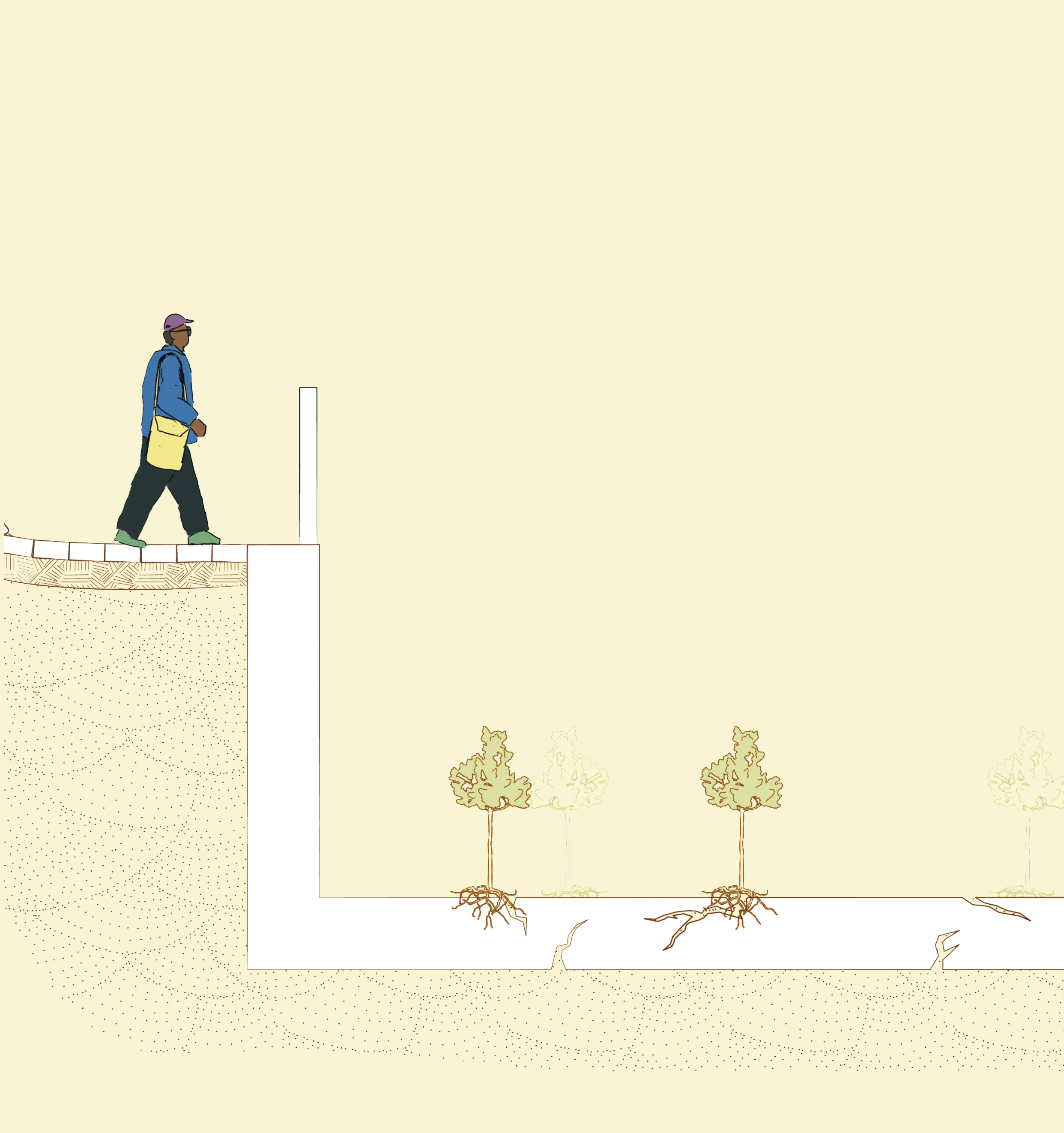

As you cross the NCC to Oscar Peterson Park, sunken walkways simulate the feeling of a well-loved path and shepherd passersby around raised planting beds so as to not disturb the process of phytoremediation. This proposal relies entirely on the use of crops native to Quebec to facilitate both recovery and nourishment of the soil. Plants from varying classifications are employed depending on their inherent ability to mitigate toxins.

In the case of most urban soils, the targeted contaminants include lead, arsenic, cadmium, and copper.

A chart categorizing types of plants and their ability to reduce toxins from soil

Progress is dependant on engagement and the community as an active participant throughout. From soil preparation and clean up in the beginning; to propagation, planting, and harvesting; to finally composting of the toxic plants, the community is involved at every stage. While an agricultural organization may provide guidance, it is through the community’s initiation that the land begins to heal.

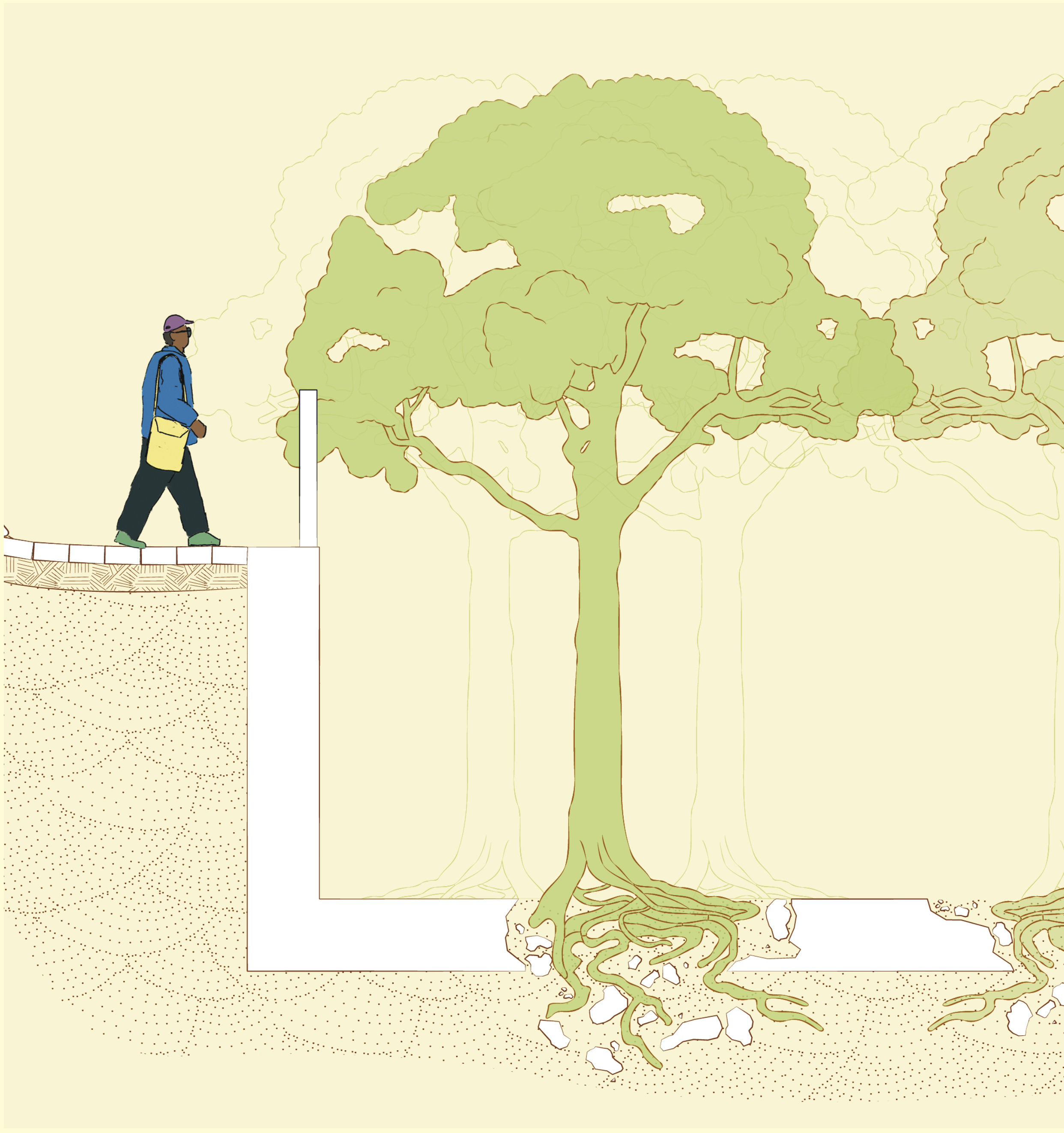

The site of the NCC requires particular attention as remains of its former foundations occupy the lot. While still honouring its longstanding presence, the site is transformed for modern use by planting young quaking aspen trees (Populus tremuloides) where cracks have formed. These trees typically fare well in low soil environments as their wide and deep root system continually spreads out in search for soil. As the tree matures, pressure from the ever-growing roots causes cracks within the foundation to grow and fragment, revealing the soil beneath for remediation.

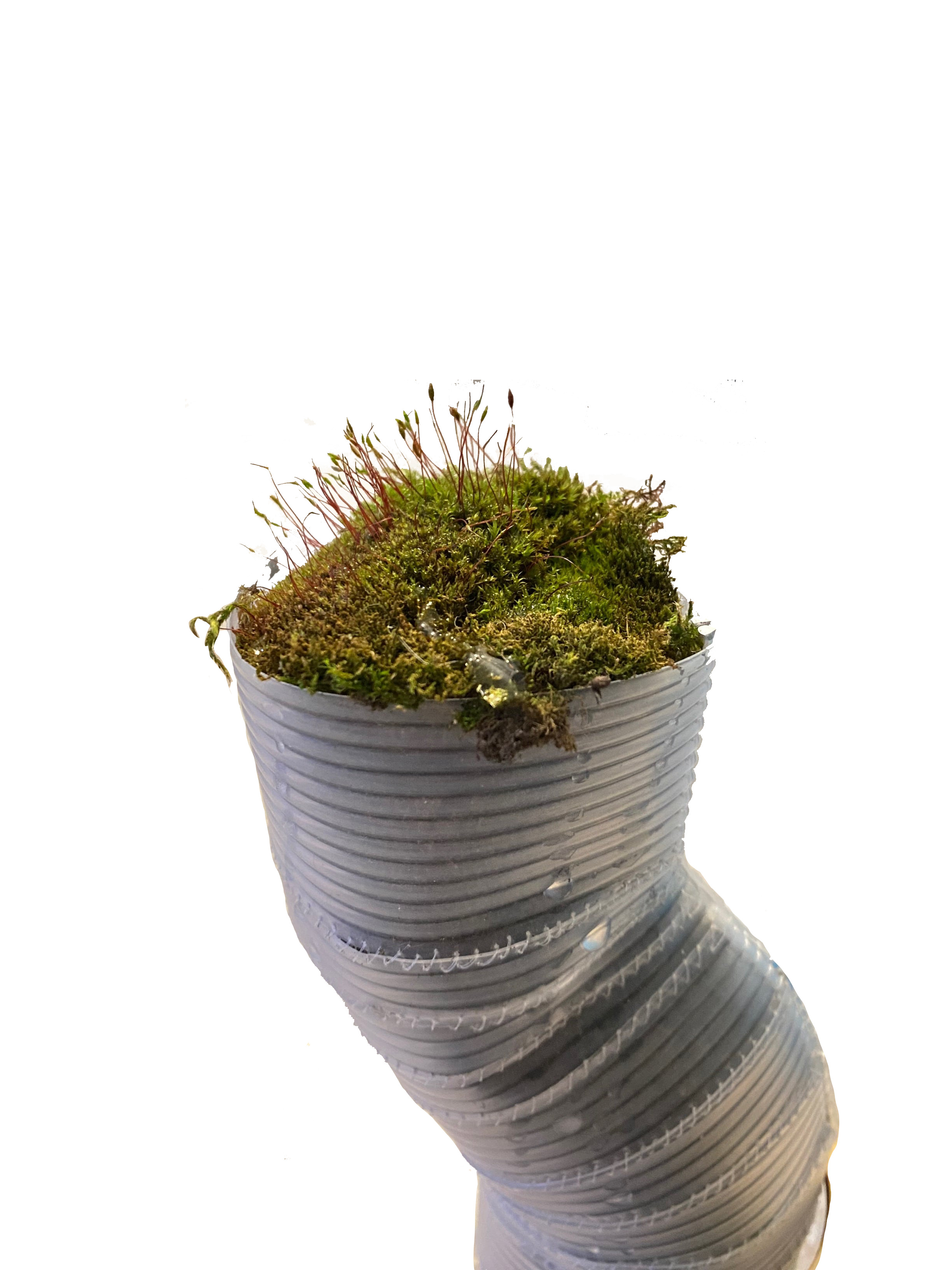

Pinto beans grown using soil from the site

〰

people

Along this journey, little moments invite you to disembark from the path. Beginning at the NCC where the footprint of the former centre welcomes you, the path then takes you through a series of rooms. Each of these spaces is arranged with playground-like planters to encourage reflection and communication. In a form of “expedited phytoremediation”, these soil columns are remediated quicker (due to their smaller volume) and able to sustain food

—demonstrating each stage of the process along with providing a glimpse of the future to the public. Dots of freshly grown food sprawl across the landscape and create this vision of a potential future where the entire plot of land offers a cornucopia of fresh produce in hopes to engage community involvement and investment.

The NCC marked the early stages of a community coming together in Little Burgundy. Offering a space for cultural preservation, it provided relief and established a sense of self-reliance against an oppressive system. Now nine years after its demolition,

Remediation Gardens aims to address the current issues of food inequity faced by Little Burgundy through engaging in communal proactivity. This reparative act of localizing agriculture and food distribution on the site of wreckage allows the community to refamiliarize itself with its land along with different tools to provide relief.