McGill School of Architecture MSoA — ARCH673

Memory and Future

Architecture of Community Space

“Architecture has the potential to do more than resolve a set of problems: it can establish what requires attention today.”

- The Other Architect, CCA

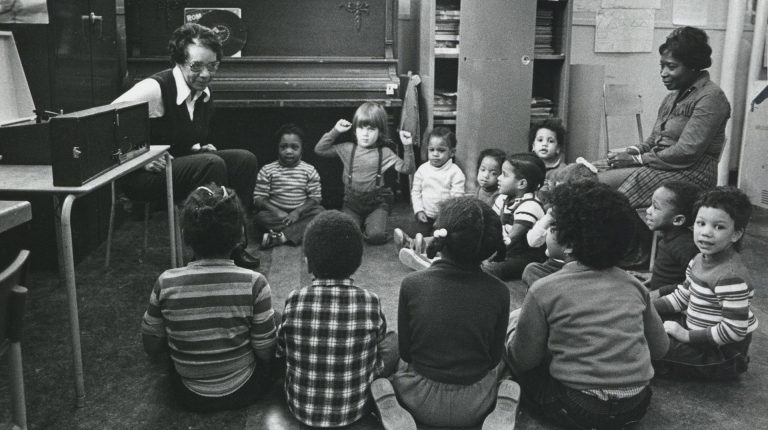

The design of a community-centered environment that is rooted in Montreal’s Black communities has the potential to act as a space of living memory. A space rooted in history while addressing current and future challenges. This act of remembrance, specifically as it relates to the complexities of the site, the neighbourhood and the presence of Black communities in the Americas, presents an opportunity to reflect on a critical architectural discourse. Through an architectural lens, the studio will engage with topics including gentrification, post-colonialism, reparations, community-led design and Afro-futurism. The building housing the NCC, located at 2035 rue Coursol, was initially constructed in 1890 as the West End Methodist Church. The NCC, founded at the Union United Church in the 1920s, was an active and significant Community Centre serving the city's Black community. It operated on Rue Coursol from its merger with the Iverley Community Centre in 1955 until 1993. The center included offices, a gymnasium, a sewing room, a kitchen, a library, and the Walker Credit Union office. The center, both at this site on Coursol and at its original home, was a hub for the community and supported jazz greats Oscar Peterson, Oliver Jones, and teacher Daisy Sweeney. It initially focused on youth programming and eventually hosted a daycare, summer camps, dance and music lessons, after-school programs, a seniors program, and language courses.

1980s : A Music Class With Daisy Sweeny

What community-based future can exist for a site of significant cultural relevance, for a community impacted by gentrification and displacement?

This studio will strive to move beyond the basic understanding of a site to form a relevant

architectural concept. The goal is rather to immerse ourselves in all aspects of the site, the people and the stories that compose this unique environment. It will be a new way of thinking about how architecture can impact, first and foremost, the social environment; how it can reach in and touch people on a personal level—provoking emotion, connection, action and reaction. This requires talking to the community in the first place, understanding what unites them and

involving them in the process and the outcome.

The concept of placemaking within the world of architecture and urban design gained popularity in the 1960s, not coincidentally around the same time period when the space of the NCC would have been thriving. Placemaking is about designing cities that cater to people and the importance of lively neighbourhoods and inviting public spaces. It is also about shifting the power dynamic of design away from the tabula rasa approach of modernist architecture, back towards the human scale. It is an approach that requires adventuring out into the real world, looking closely at ordinary scenes and events, seeing what they mean, and seeing whether any common threads emerge among them.

Author and placemaker Jay Pitter has identified that in her practice, she is, “constantly interrogating the ways spaces facilitate or impede the movement, wellness, and possibility of urban dwellers. Unlike traditional placemaking practice, I explicitly address the increasing stratification in cities. I recognize that people’s experiences in cities are informed by varying levels of spatial entitlement, histories of displacement, bodies being “read” differently in the public realm, and systemic exclusion.

Danish architect and urban designer Jan Gehl said, "First life, then spaces, then buildings – the other way around never works"; and "In a Society becoming steadily more privatized with private homes, cars, computers, offices and shopping centers, the public component of our lives is disappearing. It is increasingly important to make the cities inviting, so we can meet our fellow

citizens face to face and experience directly through our senses. Public life in good quality public spaces is an important part of a democratic life and a full life."

Every creative placemaking project, by definition, is different and tells a distinctive story about its inspiration, location, and community. This approach is especially true for projects that tap into an as-yet-uncovered story, or a story that has been washed over by urban renewal, gentrification and social and racial inequalities. Urban design is not neutral, it can perpetuate or it can resolve urban inequity. Public spaces are a direct reflection of this. Meaningful public spaces can and

should be places that empower people, where stories and histories are exchanged and shared and where relationships can be made across differences.

Achieving these meaningful places however can be challenging if we exclusively rely on the means of planning or architecture. The relatively new field of Narrative Environments has anchored itself within the design community as a practice that transcends any one discipline, bringing together ideas across architecture, communication design, interaction design, scenography and curation. According to Tricia Austin, Director of the MA in Narrative. Environments at Central Saint Martins in London, “The design of narrative environments involves a deliberate and coordinated three part sequence of movement: the progression of content, through space and over time, in order to tell a story and communicate a message or messages to particular audiences. In narrative environments, stories are not just overlain on a space; they are embedded in and expressed through form and materiality.” Narrative environments offer the opportunity for public spaces to actively and intentionally do more. They can provide commentaries, probe dominant histories and seek ways to enhance the agency of individuals and groups in civil society.

The theories and approaches of both Placemaking and Narrative Environments help to contextualize the work we will do this semester on the site of the former NCC. The NCC is a place that lives on now only in memory. It was a lively and dynamic community space, one that not only played a significant role in people’s everyday lives, but also as a gathering place for groups battling racial prejudice in the mid 20th century, representing justice and freedom for the community.

architectural concept. The goal is rather to immerse ourselves in all aspects of the site, the people and the stories that compose this unique environment. It will be a new way of thinking about how architecture can impact, first and foremost, the social environment; how it can reach in and touch people on a personal level—provoking emotion, connection, action and reaction. This requires talking to the community in the first place, understanding what unites them and

involving them in the process and the outcome.

The concept of placemaking within the world of architecture and urban design gained popularity in the 1960s, not coincidentally around the same time period when the space of the NCC would have been thriving. Placemaking is about designing cities that cater to people and the importance of lively neighbourhoods and inviting public spaces. It is also about shifting the power dynamic of design away from the tabula rasa approach of modernist architecture, back towards the human scale. It is an approach that requires adventuring out into the real world, looking closely at ordinary scenes and events, seeing what they mean, and seeing whether any common threads emerge among them.

Author and placemaker Jay Pitter has identified that in her practice, she is, “constantly interrogating the ways spaces facilitate or impede the movement, wellness, and possibility of urban dwellers. Unlike traditional placemaking practice, I explicitly address the increasing stratification in cities. I recognize that people’s experiences in cities are informed by varying levels of spatial entitlement, histories of displacement, bodies being “read” differently in the public realm, and systemic exclusion.

Danish architect and urban designer Jan Gehl said, "First life, then spaces, then buildings – the other way around never works"; and "In a Society becoming steadily more privatized with private homes, cars, computers, offices and shopping centers, the public component of our lives is disappearing. It is increasingly important to make the cities inviting, so we can meet our fellow

citizens face to face and experience directly through our senses. Public life in good quality public spaces is an important part of a democratic life and a full life."

Every creative placemaking project, by definition, is different and tells a distinctive story about its inspiration, location, and community. This approach is especially true for projects that tap into an as-yet-uncovered story, or a story that has been washed over by urban renewal, gentrification and social and racial inequalities. Urban design is not neutral, it can perpetuate or it can resolve urban inequity. Public spaces are a direct reflection of this. Meaningful public spaces can and

should be places that empower people, where stories and histories are exchanged and shared and where relationships can be made across differences.

Achieving these meaningful places however can be challenging if we exclusively rely on the means of planning or architecture. The relatively new field of Narrative Environments has anchored itself within the design community as a practice that transcends any one discipline, bringing together ideas across architecture, communication design, interaction design, scenography and curation. According to Tricia Austin, Director of the MA in Narrative. Environments at Central Saint Martins in London, “The design of narrative environments involves a deliberate and coordinated three part sequence of movement: the progression of content, through space and over time, in order to tell a story and communicate a message or messages to particular audiences. In narrative environments, stories are not just overlain on a space; they are embedded in and expressed through form and materiality.” Narrative environments offer the opportunity for public spaces to actively and intentionally do more. They can provide commentaries, probe dominant histories and seek ways to enhance the agency of individuals and groups in civil society.

The theories and approaches of both Placemaking and Narrative Environments help to contextualize the work we will do this semester on the site of the former NCC. The NCC is a place that lives on now only in memory. It was a lively and dynamic community space, one that not only played a significant role in people’s everyday lives, but also as a gathering place for groups battling racial prejudice in the mid 20th century, representing justice and freedom for the community.

How can its story and spirit contribute to a new proposition, a new narrative, that resonates with our times’ evolving challenges and opportunities?

The studio, held during the winter session of the professional Master's program in architecture at the "Peter Guo-Hua Fu School of Engineering" at McGill University, aimed to study the sociospatial context of Little-Burgundy, and more specifically, around the NCC site. The research and consultation process with the community, led by instructors and professionals Shane Laptiste and Rebecca Taylor, resulted in a proposed program and project outline to reactivate the abandoned site. This collection of ideas serves as a foundation on which to develop a real project that addresses the specific needs of Little-Burgundy’s community.