The City Below The Ville Marie

“By the 1950s, the automobile was seen by certain critics as the great destroyer of cities [...] destroying many essential urban qualities, including human scale and continuity.”

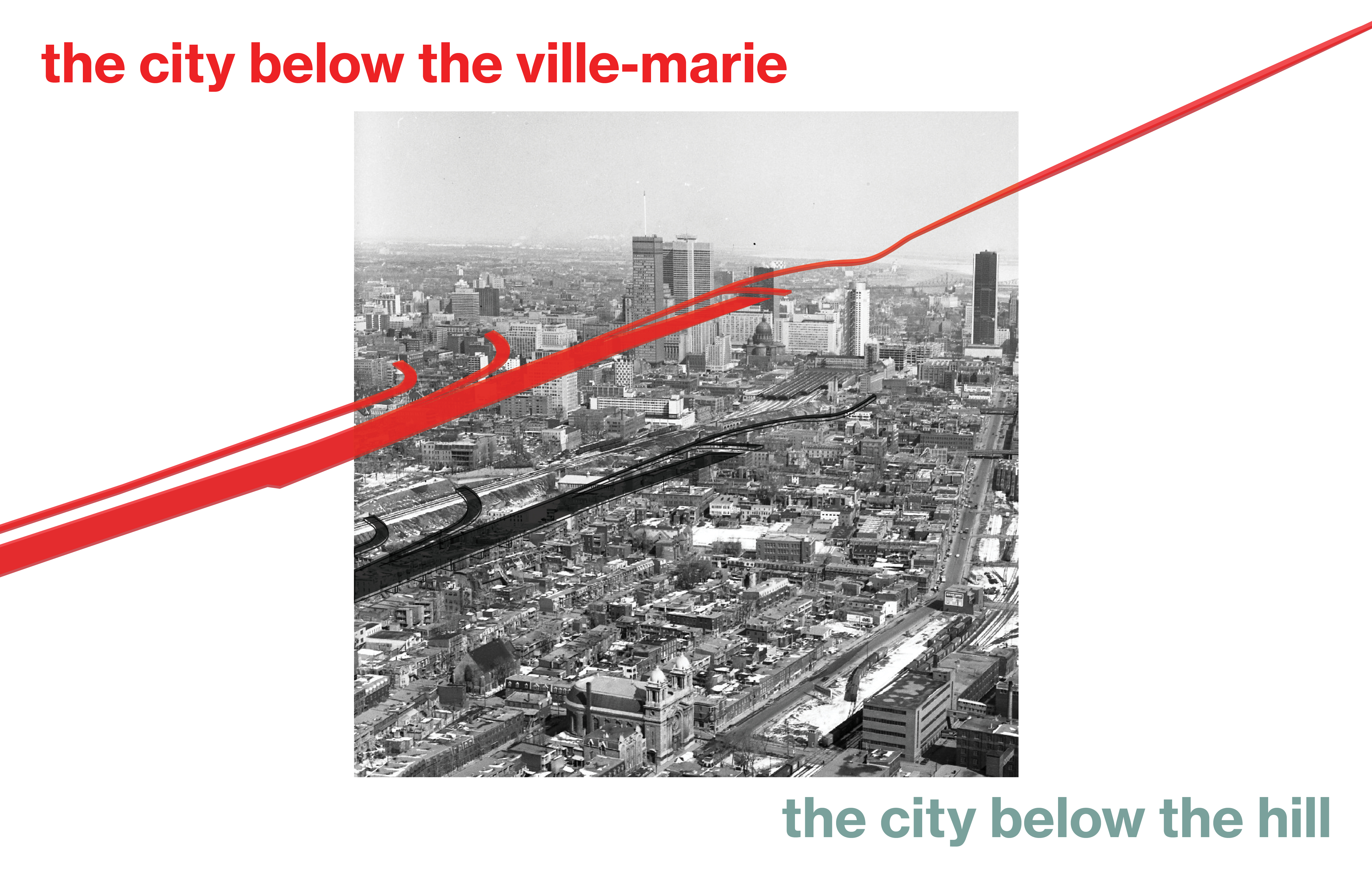

Between 1967 and 1973, the

Ville-Marie expressway was constructed to connect the East and West by slicing

through Little Burgundy and Chinatown further east.

The shift away from railway transportation led to a focus on connecting majority-white suburban workers and consumers to the downtown core. Post-war North America considered the expressways as a tool to: decongest inner city traffic, connect major sectors within the city, and carve a bypass route through the city.

The elevated expressway was intended to open up land for urban rehabilitation and provide a new aesthetic experience of the city through uninterrupted movement for automobile drivers.

Planners of the Ville-Marie Expressway encountered a mixed response as they attempted to choose ‘the path of least resistance’, but nonetheless destroyed residential neighbourhoods and small businesses. The highway expropriation had a disproportionate impact on black Montrealers which led to the eventual closure of community institutions that served the community.

The shift away from railway transportation led to a focus on connecting majority-white suburban workers and consumers to the downtown core. Post-war North America considered the expressways as a tool to: decongest inner city traffic, connect major sectors within the city, and carve a bypass route through the city.

The elevated expressway was intended to open up land for urban rehabilitation and provide a new aesthetic experience of the city through uninterrupted movement for automobile drivers.

Planners of the Ville-Marie Expressway encountered a mixed response as they attempted to choose ‘the path of least resistance’, but nonetheless destroyed residential neighbourhoods and small businesses. The highway expropriation had a disproportionate impact on black Montrealers which led to the eventual closure of community institutions that served the community.

In

January of 1971, a coalition of 14

groups that included high profile advocacy bodies and local community

associations emerged with the shared conviction that funding should be diverted

to other infrastructure such as housing, the Metro, and sewage and sanitation

systems rather than on the construction of the highway. Some prominent

community activists that objected the construction of the expressway include

Joseph Baker, director of the community design workshop at the McGill School of

Architecture, Guy Dupuis of the Montreal Labour Council and Quebec Federation

of Labour, Michel Lize, member of the Front d’Action Politique, and Michel

Bourdon of the Montreal Council of the Confederation of National Trade Unions.

Other local groups that mobilized against the route included the Lower

Westmount Citizens’ Committee (LWCC), the Housing and Urban Renewal Committee

(HURC), and citizens committees from Lower Westmount, Little Burgundy,

Maisonneuve, and St. Jacques.

Today’s Rue Saint Antoine, adjacent

to the expressway, with its one-way traffic flow is designed to push cars as

quickly as possible to and from the highway. So, the street lost its pedestrian

friendliness despite the wide green sidewalks.

![]() In comparison, in the past, Saint

Antoine was an active street where at one time, was inhabited by working class

families and various businesses. By the 1950s, streetcars (tramways) began to

be replaced by buses and the city’s transportation system was starting to be

prioritized in hopes to make Montreal a modern city. With Expo 67 coming, Mayor

Drapeau led the city to embark on rapid modernization projects like the highway, the metro and slum clearances.

In comparison, in the past, Saint

Antoine was an active street where at one time, was inhabited by working class

families and various businesses. By the 1950s, streetcars (tramways) began to

be replaced by buses and the city’s transportation system was starting to be

prioritized in hopes to make Montreal a modern city. With Expo 67 coming, Mayor

Drapeau led the city to embark on rapid modernization projects like the highway, the metro and slum clearances.

In comparison, in the past, Saint

Antoine was an active street where at one time, was inhabited by working class

families and various businesses. By the 1950s, streetcars (tramways) began to

be replaced by buses and the city’s transportation system was starting to be

prioritized in hopes to make Montreal a modern city. With Expo 67 coming, Mayor

Drapeau led the city to embark on rapid modernization projects like the highway, the metro and slum clearances.

In comparison, in the past, Saint

Antoine was an active street where at one time, was inhabited by working class

families and various businesses. By the 1950s, streetcars (tramways) began to

be replaced by buses and the city’s transportation system was starting to be

prioritized in hopes to make Montreal a modern city. With Expo 67 coming, Mayor

Drapeau led the city to embark on rapid modernization projects like the highway, the metro and slum clearances.

The consequences of the Ville-Marie

expressway were the closing down of buildings and facilities, and the relocation

of residents.

Present and Past Conditions

Present and Past Conditions

(1) The demolition of the strip between Saint

Antoine and the escarpment heavily prioritizes the flow of cars over

pedestrians. Even with wide sidewalks and a bike lane, the street is not as

animated due to the lack of active frontages at street level.

Statistics have shown that neighbourhoods are generally gentrified especially around metro stations. In Little Burgundy, homes have remained relatively affordable around Georges-Vanier metro but it is the only station that is not served by any bus lines and was ranked the least busy in terms of passenger entries in 2019. Today’s condition does not promote a lived-in street experience.

Statistics have shown that neighbourhoods are generally gentrified especially around metro stations. In Little Burgundy, homes have remained relatively affordable around Georges-Vanier metro but it is the only station that is not served by any bus lines and was ranked the least busy in terms of passenger entries in 2019. Today’s condition does not promote a lived-in street experience.

(2) In the past, there wasn’t much

visual obstruction from the north of the railway line and Little Burgundy.

Today, looking south from the Canadian Centre of Architecture’s sculpture

garden, the expressway conceals the neighbourhood.

(3) Similarily, looking north from Rue Saint-Antoine, there is a visual obstruction from past and present looking north.

(4) The urban form east of the NCC no longer looks the same. Due to changes in the neighbourhood, the city’s entertainment industry along the East of Saint Antoine like Rockhead’s Paradise, ceased operation. Many black-owned businesses also suffered as the new and renovated housing development has little commercial space. The NCC was backed behind the major street of Saint Antoine and it presently lost a lot of its historical character.

(3) Similarily, looking north from Rue Saint-Antoine, there is a visual obstruction from past and present looking north.

(4) The urban form east of the NCC no longer looks the same. Due to changes in the neighbourhood, the city’s entertainment industry along the East of Saint Antoine like Rockhead’s Paradise, ceased operation. Many black-owned businesses also suffered as the new and renovated housing development has little commercial space. The NCC was backed behind the major street of Saint Antoine and it presently lost a lot of its historical character.

Before the Ville-Marie Expressway,

Rue Saint-Antoine was an artery that connected the Black residents of Little

Burgundy with businesses, amenities, and essential components of community

life.

Before the expropriations, the area between Griffintown and Saint-Henri in Montreal’s Southwest were known by Saint-Antoine. Many black Montrealers would even simply call it the “West End.”

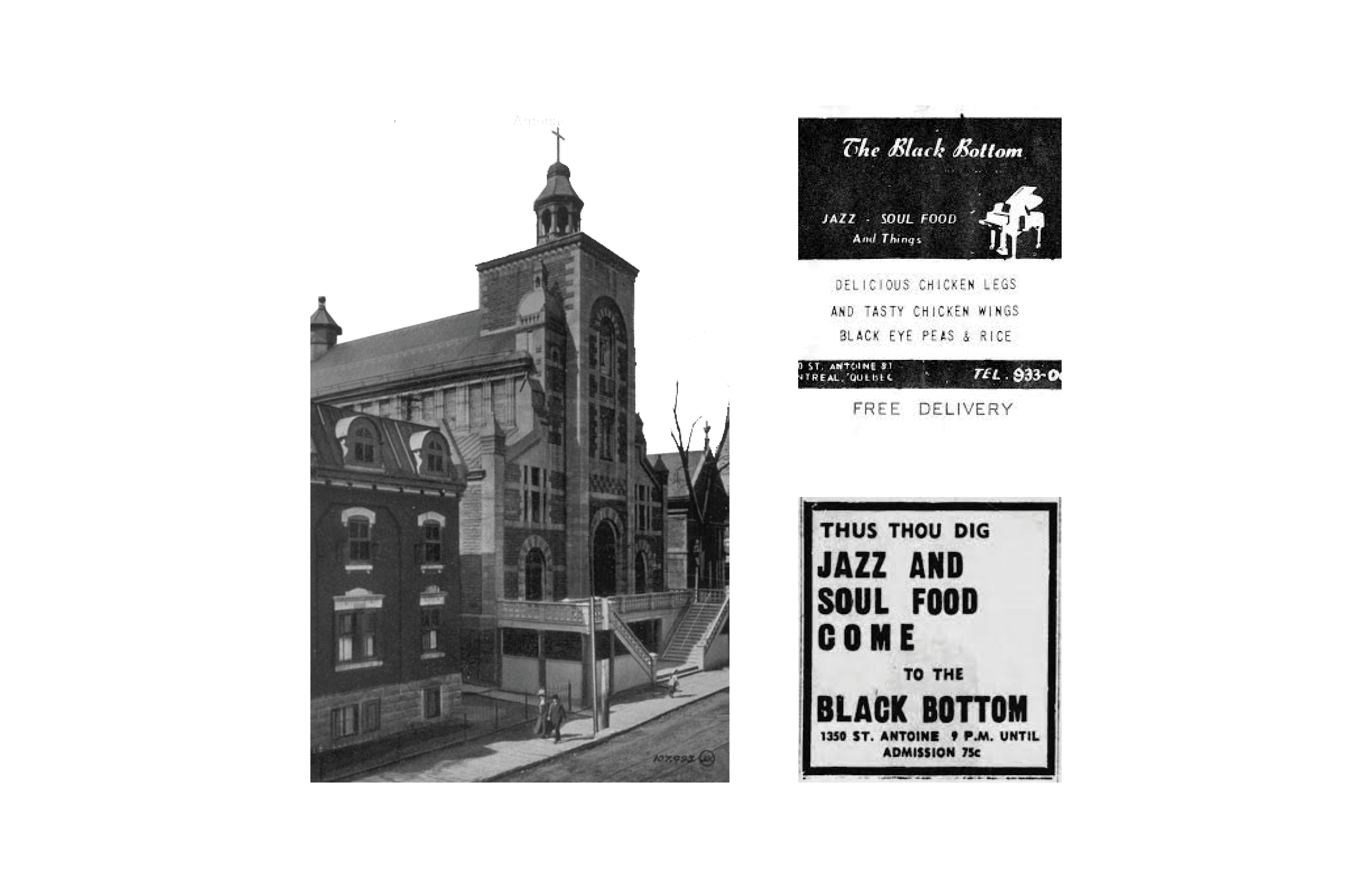

Some of the significant buildings that were demolished include St Anthony’s Church – a church and hub for community organizing and social activities, similar to the NCC, it was an institution that supported the Black community, and the Black Bottom Café. The Black Bottom Café was an after-hours jazz club that provided a meeting point for musicians and served “soul food.” As a result of the segregation in Montreal, the Black jazz musicians had no access to uptown white clubs and instead assembled clubs of their own along Saint Antoine Street. However, due to the highway and urban renewal undertaken in stages that expelled people and other businesses, the jazz clubs that remain in Montreal are all situated north of the expressway.

Before the expropriations, the area between Griffintown and Saint-Henri in Montreal’s Southwest were known by Saint-Antoine. Many black Montrealers would even simply call it the “West End.”

Some of the significant buildings that were demolished include St Anthony’s Church – a church and hub for community organizing and social activities, similar to the NCC, it was an institution that supported the Black community, and the Black Bottom Café. The Black Bottom Café was an after-hours jazz club that provided a meeting point for musicians and served “soul food.” As a result of the segregation in Montreal, the Black jazz musicians had no access to uptown white clubs and instead assembled clubs of their own along Saint Antoine Street. However, due to the highway and urban renewal undertaken in stages that expelled people and other businesses, the jazz clubs that remain in Montreal are all situated north of the expressway.

A community member said, “St. Antoine was one of the richest looking community streets you ever

want to see […] You have to see it to understand, the kind of destruction that

took place in this community.”

This research has prompted the reconsideration what could reanimate the street environment for businesses and pedestrians and promote public transit over car-use, especially with the former NCC being in such close proximity to a major street for the community.

This research has prompted the reconsideration what could reanimate the street environment for businesses and pedestrians and promote public transit over car-use, especially with the former NCC being in such close proximity to a major street for the community.