1960s – 1980s

The urban renewal project and the NCC’s golden era.

The 1960s through the 1980s represent a rich period of change for the NCC and for Little Burgundy neighbourhood.

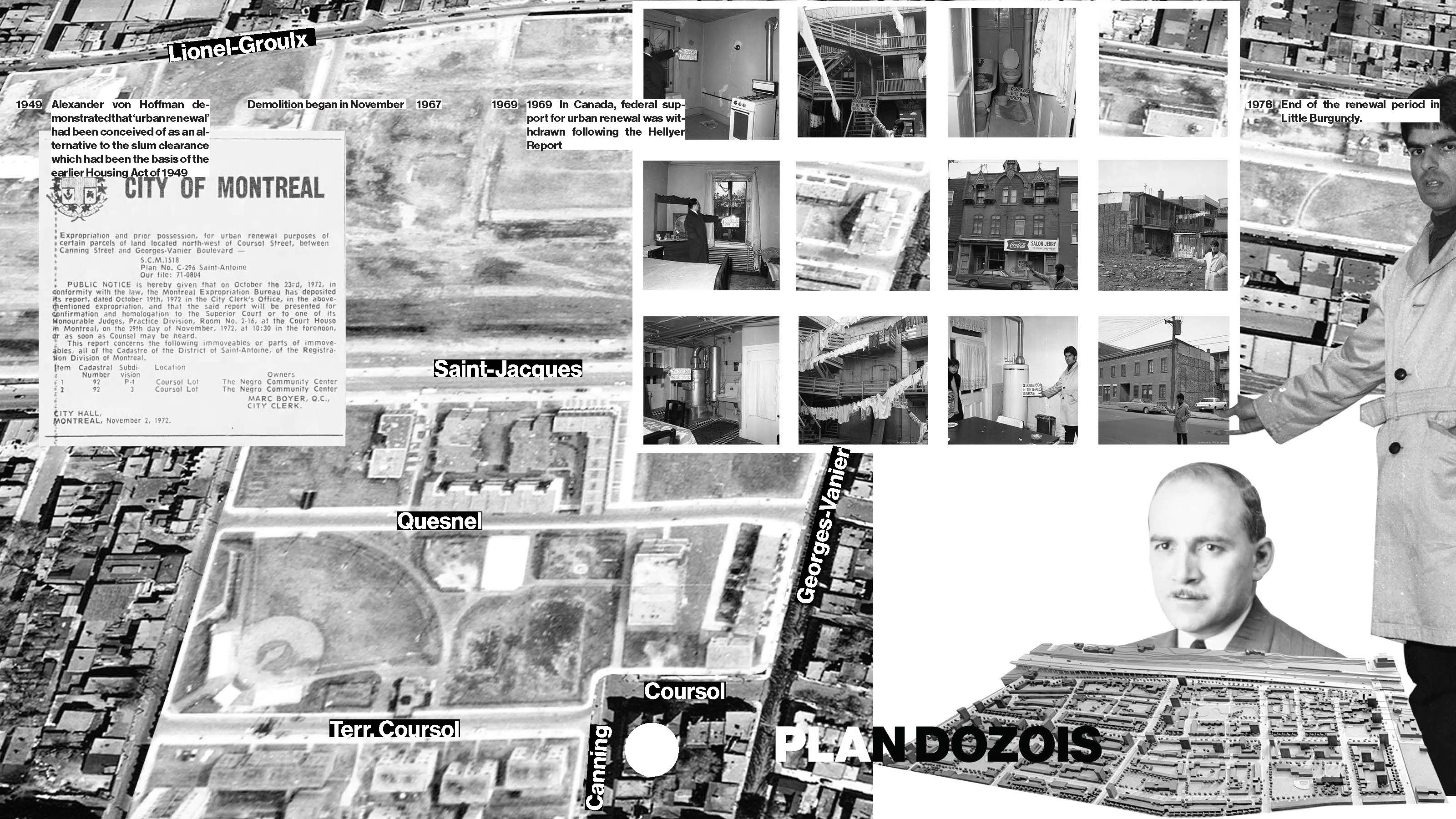

The 1960s through the 1980s represent a rich period of change for the NCC and for Little Burgundy neighborhood. The NCC arrived in 1955 at its location on Rue Coursol and this period of 20 years represents the golden era of the institution. The jazz scene was still prominent in Little Burgundy at the beginning of these years, even though the most flourishing years were before the end of the Second World War. During the 1960s, the neighborhood was in a generally poor state and basic needs were not met, leading to a letter from the priests of Montreal’s Sud-Ouest protesting the inhuman condition, prevailing as “cold flats” were still common use.

Under the mayor, Jean Drapeau, and through the construction of new highways, the metro, and urban renewal project, Montreal entered in an era of “modernization”. The work was intended to improve the city through the “renovation” of poor neighborhoods. Unfortunately, Little Burgundy became one of the targeted areas.

Against fierce citizen contestation that discredited the planning project that was developed without the input of the residents, the urban renewal project started in December 1966 by the expropriation of families living on the Ilôt Saint Martin.

In the aftermath of the urban-renewal project, the ‘crack crisis’ that peaked around 1990 ravaged the neighbourhood. Security and safety became an issue for the residents, as drug use and trafficking brought violent crimes onto the streets of Little Burgundy.

Under the mayor, Jean Drapeau, and through the construction of new highways, the metro, and urban renewal project, Montreal entered in an era of “modernization”. The work was intended to improve the city through the “renovation” of poor neighborhoods. Unfortunately, Little Burgundy became one of the targeted areas.

Against fierce citizen contestation that discredited the planning project that was developed without the input of the residents, the urban renewal project started in December 1966 by the expropriation of families living on the Ilôt Saint Martin.

In the aftermath of the urban-renewal project, the ‘crack crisis’ that peaked around 1990 ravaged the neighbourhood. Security and safety became an issue for the residents, as drug use and trafficking brought violent crimes onto the streets of Little Burgundy.

Since 1955, the NCC had been located at 2035 Coursol. At this time, the 90% Black membership of the NCC merged with the 100% White membership of the Iverley League. Between 1955 and 1958, the NCC received donations and funding that allowed them to improve the building for their needs as well as expanding the program to include citizenship education, adult programming, and local affairs issues. The programming became quite extensive and went beyond the wall of the NCC. Any demographic could find a fitting activity.

Many members of the Black community were greatly involved in the activities at the NCC. Sweeney Peterson was one of them: “[Sweeney] would get someone to loan them a piano, or she’d persuade a service club to donate a piano to the center and then she’d have it installed in their home. When times were tough, she’d even see that they had clothing to wear. She was a tremendous influence on people in the community, but it was always behind the scenes.”

Many members of the Black community were greatly involved in the activities at the NCC. Sweeney Peterson was one of them: “[Sweeney] would get someone to loan them a piano, or she’d persuade a service club to donate a piano to the center and then she’d have it installed in their home. When times were tough, she’d even see that they had clothing to wear. She was a tremendous influence on people in the community, but it was always behind the scenes.”

Originating from the US, where it was codified in the Housing Act of 1954, urban-renewal projects had dramatic effects on the resident of Little Burgundy. The superposition of the map from 1949 with parts of the one from 1973 shed light on the changes that affected the urban fabric of the neighbourhood.

People had to be moved during the demolition and construction, fracturing the community at its core. Relocating the displaced residents was often a difficult task in the context of housing shortages and the project took more than a decade to come to completion, depriving Black residents of a place to live in Little Burgundy and beyond.

People had to be moved during the demolition and construction, fracturing the community at its core. Relocating the displaced residents was often a difficult task in the context of housing shortages and the project took more than a decade to come to completion, depriving Black residents of a place to live in Little Burgundy and beyond.